Cornus canadensis L.

|

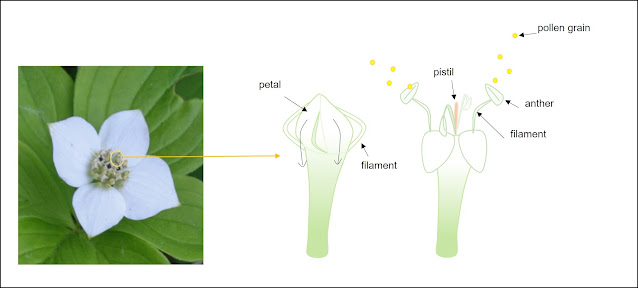

| Bunchberry, Cornus canadensis, flowering in northern Minnesota in mid-June 2022. |

Also called Canada dogwood or creeping dogwood, bunchberry

is a patch-forming, herbaceous plant of cool, moist forests. Although it’s

related to red osier dogwood (C. sericea), gray dogwood (C. racemosa)

and similar shrubs, this plant has no aboveground woody growth. Mature plants are

just 3-6 inches tall, their short stems tipped by four to six, arc-veined

leaves that are so closely spaced they appear whorled.

In late spring or early summer, mature plants produce a

cluster of 12-40 small flowers surrounded by four white bracts. The petals of

the flowers are just 1-2 millimeters long (1) and fused along their edges until

they open.

The stamens of the flowers grow quickly, faster than the

petals. As they mature, their anthers, the pollen-producing tips of the stamens,

are trapped inside the closed flowers, but their lengthening filaments bend

outward between the petals. Eventually, a trigger – a visiting bumblebee, for

example, or the building pressure within the flower– causes the flowers to open explosively. As the

petals flip back, the stamens spring outward, and pollen is catapulted into the

air (2,3). The grains can be lofted as high as 2.5 centimeters (25 millimeters)

above the flower, ten times the height of the flower itself (3).

[Watch a video of an exploding flower here.]

If they’re launched at high enough speed, some of the pollen

may catch in the hairs of flying insects, which then carry it to other

plants. Other pollen rides the wind. Unlike plants that are pollinated only by

insects, bunchberry pollen grains are smooth instead of sticky, and so more easily carried by a breeze (2).

A dual system of pollination is an advantage for bunchberry.

These low-growing plants are self-incompatible, so they need pollen from other

plants to form seeds. If insect pollination isn’t successful, wind pollination might

be, but for the latter to work, pollen must be launched high enough to be wafted

over a patch of the plants.

If either method of pollination succeeds, the plants will

produce bunches of red drupes, fruits with single, stony seeds. The fruits look

like berries, inspiring the name bunchberry.

Where to find bunchberry

Bunchberry typically grows in cool, moist broadleaf,

coniferous or mixed forests. In North America, its range is primarily the

northern tier of states, all of Canada, and Greenland (4). This circumboreal

plant is also found at northern latitudes in Asia.

More information

For photos and more information about bunchberry, see the Minnesota

Wildflowers page for this species.

References

(1) Flora

of North America, efloras.org. Accessed online on June 27, 2022. Formal

citation:

eFloras (2008). Published on the

Internet http://www.efloras.org [accessed

27 June 2022]. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard

University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

(2) Whitaker, D., Webster, L., and Edwards, J. (2007). The

biomechanics of Cornus canadensis stamens are ideal for catapulting

pollen vertically. Functional Ecology 21. 219-225. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01249.x

(3) Edwards, J., Whitaker, D.,

Klionsky, S. et al. 2005. A record-breaking pollen

catapult. Nature 435, 164 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/435164a

(4) USDA,

NRCS. 2022. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 06/27/2022). National

Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC USA.