|

| Phragmites australis subsp. americanus. Photo taken in early August in southern Minnesota. |

Update: An abbreviated ID guide (PDF) is here.

Phragmites or Common Reed, Phragmites australis, is a 12- to 18-foot tall, perennial grass of wetlands, shorelines and ditches. Two subspecies are common in the U.S. One is the native subspecies americanus; the other is the introduced subspecies australis.

Both subspecies grow in colonies, but subspecies australis

is more aggressive and can dominate habitats to the near exclusion of other

plants. For that reason, there is growing interest in identifying and mapping

subspecies australis to determine the extent of its spread and to target

those colonies for removal.

Although the subspecies look alike, there are several characteristics that, taken together, can identify one from the other. The most reliable characteristics are shown below, after a few terms used to describe grass stems, leaves and flowers.

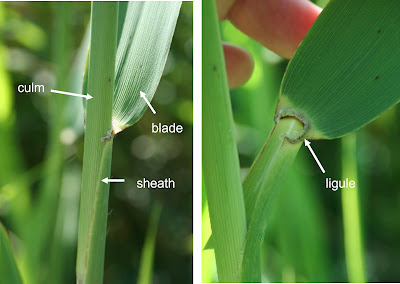

Stems and leaves

Flowers

Grass flowers, called florets, are specialized for wind

pollination. Each floret is composed of two narrow bracts, a lower lemma and an upper palea.

Stamens and feathery stigmas emerge from between them.

Florets are arranged in small spikes called spikelets. At the base of each spikelet are two bracts called glumes. Glume length differs between the subspecies of Phragmites. More on that in a following section.

Spikelets of Smooth Brome, Bromus inermis, are shown below. On the left are spikelets with brown anthers and feathery, white stigmas emerging from individual florets. On the right is a single spikelet spread apart to see the florets and glumes. The spikelets are about 3 cm (1.5 in.) long.

Phragmites characteristics

To identify Phragmites subspecies, it’s best to look at more than one plant in a colony and at several characteristics of each plant. Hybrids are possible, but they’re said to be rare.

Ligules

To see ligules, pull back a blade from the middle third of the culm. (Ligules may be immature on the upper third of the culm and degraded on the lower third.) Ligule length differs between the subspecies.Sheaths

In late summer, fall and early winter, examine the lower stem for the presence of leaf sheaths. The photos below are from mid-November.Subspecies americanus: Sheaths are absent or easily removed.

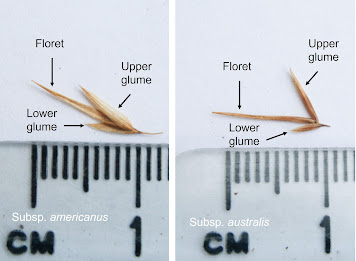

Glumes

In late summer and fall, measure glume length. By late fall some of the florets may be gone, but the glumes often persist. It's best to look at several pairs of glumes to get an idea of their average length. The photos below are from mid-November.Subspecies americanus: Lower glume 3-6 mm long (most > 4mm); upper glume 5-11 mm long (most > 6 mm).

Look-alikes

Amur Silver Grass and Reed Canary Grass are two smaller grasses that can be mistaken for Phragmites.Chadde, S.W. 2012. Wetland Plants of Minnesota. 2nd

edition (revised). A Bogman Guide.

Judziewicz, E. J., Freckmann, R.W., Clark, L.G., and Black,

M.R. 2014. Field Guide to Wisconsin Grasses. The University of Wisconsin Press,

Madison.

Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center (MAISRC).

Identifying invasive Phragmites.

Website accessed July 2022.

Swearingen, J., Saltonstall, K., and Tilley, D. Phragmites

Field Guide: Distinguishing Native and Exotic Forms of Common Reed (Phragmites

Australis) in the United States. Technical Note Plant Materials 56, October

2012. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Boise, ID.