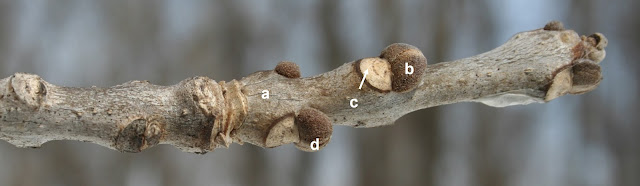

Tip #1: If they're within reach, look at twigs.

- Alternate: One bud per node

- Opposite: Paired, or two buds per node

- Subopposite: Paired but not quite opposite

- Whorled: Three buds per node

Tip #2: Within leaf scars, look for vascular bundle scars.

Tip #3: Look at bark.

Bark color and texture are helpful clues but can change with age. Also look for lenticels, spots or irregular shapes on the bark of younger trees or shrubs. In the photographs of Green Ash below, lenticels are the white spots on the reddish-brown bark of the sapling shown on the left (arrows).

On the right is a mature Green Ash showing the typical honeycomb-like pattern of ridges and furrows of its bark.

Tip #4: Look for overwintering fruit.

Some species retain their fruits, or parts of them, well into winter. Also look under the shrub or tree for fruits that may be on the ground or on top of the snow.

Clockwise from top left: Red capsule walls of Winged Burning Bush, Euonymus alatus; samaras of Box Elder, Acer negundo; pods of Kentucky Coffee Tree, Gymnocladus dioicus, each 3 to 4 inches (7-10 cm) long; and the fruits of Amur Cork Tree, Phellodendron amurense.

Tip #5: A few species hold on to their leaves.

Some trees are marcescent -- their leaves turn brown but aren't shed in fall. In this region, oaks (Quercus), Ironwood (Ostrya virginiana) and Blue Beech (Carpinus caroliniana) are among the few trees that are marcescent.

Below is Ironwood, an understory tree that retains its leaves through winter.

Tip #6: Remember MAD Cap Buck Horse.

Bud arrangement -- alternate, opposite, subopposite or whorled -- can quickly narrow choices for identification. One way to remember which species have an opposite arrangement is the mnemonic MAD Cap Buck Horse:

M Maples (Acer)

A Ash (Fraxinus)

D Dogwoods (Cornus, except for alternate-leaved dogwood, C. alternifolia)

Cap Plants that are or were in the family Caprifoliaceae, including honeysuckles (Lonicera), wolfberry or snowberry (Symphoricarpos), elderberry (Sambucus) and viburnums (Viburnum).

Buck Horse Ohio Buckeye (Aesculus glabra) and Horse Chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum)

Although this mnemonic is helpful, it doesn't include all trees and shrubs with opposite buds. For example, Wahoo and Burning Bush, genus Euonymus, also have opposite buds. So does Bladdernut, Staphylea trifolia, an understory shrub.

Most remaining species have alternate buds. Common Buckthorn, Rhamnus cathartica, is unusual in having subopposite buds. Catalpa, another unusual species, has whorled buds.

Tip #7: Look at the pith.

The pith is the center of a branchlet or twig. The appearance of the pith -- hollow or solid, color, texture -- can help confirm the identity of a tree or shrub. For example, honeysuckle shrubs (Lonicera, left photo below) have hollow piths, and Red Elderberry (Sambucus racemosa, right photo below) has a soft, yellow pith.

Tip #8: Try these guides.

The

LEAF Program from UW-Stevens Point is a K-12 forestry education initiative

that offers many online resources. Under Curriculum & Resources, choose

LEAF Tree Identification Tools. The LEAF Winter Tree ID Key is available there

as a downloadable PDF.

Pocket

Reference for Winter Tree Identification. Champaign County Forest

Preserves, Mahomet, IL.

Fruit and Twig Key to Trees and Shrubs, by William M. Harlow, PhD. Reprint edition, 1959. Dover Publications, Inc., New York. ISBN 0-486-20511-8.