|

| A sweat bee (genus Lassioglossum) on swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is in a precarious position. |

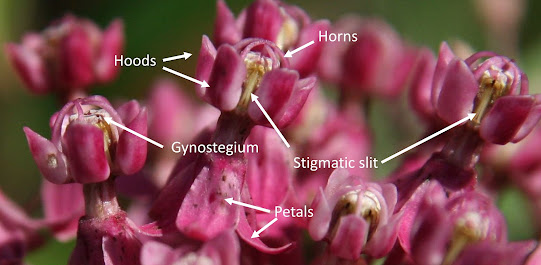

Milkweeds are familiar to many as essential for Monarch butterflies, but there’s much more to their story. A close look at their flowers shows an intricate structure with a tricky way to snag insects – literally.

The flowers of swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata),

like many other milkweeds, are composed of five reflexed petals, five upright

hoods, and five narrow horns around a gynostegium, a central column of fused

stamens and pistils. The bases of the hoods hold nectar, and between them are narrow

slits bordered by two “guide rails.” Each slit leads to a chamber that contains

the reproductive parts of the flower, including the stigma, the part that

receives pollen. For that reason, it’s called the stigmatic chamber.

What’s missing from the flowers are anthers shedding dust-like pollen grains. Unlike typical flowers, milkweeds don’t offer individual grains for insects to carry away. Instead, their pollen is packed into waxy sacs called pollinia. Each chamber holds two pollinia connected by a pair of arms and a central gland or corpusculum, Latin for “little body.” The whole structure, called a pollinarium, looks like a small pair of winged maple seeds.

Pollinia are rare. Only orchids also make them. The

advantage of packing pollen grains together is that they can be carried as one

unit to deliver hundreds of grains to the stigma of another flower. That

improves the odds that every ovule in an ovary will be fertilized and develop

into a seed.

[Sidebar: In seed plants, ovules contain egg nuclei and develop into seeds. One or more ovules reside in an ovary, which sits at the base of a pistil, the “female” reproductive part. Above the ovary is a neck-like style and the stigma, the surface that receives pollen. Ovary walls develop into fruits.]

The challenge for milkweeds is to somehow get the pollinia out of the chamber and onto another flower. To accomplish this, milkweeds rely on bees, wasps, flies and butterflies as carriers. The insects visit the flowers to get nectar, and in the process, take the pollinia. And that’s where it gets tricky.

As an insect walks across the waxy surface of a milkweed flower,

a leg or other body part can accidentally slip into one of the slits between

the hoods. The corpusculum then catches its leg, forcing the insect to pull

hard to get it out. Sometimes the insect doesn’t succeed, and it either leaves behind

a leg or dies trying to get it loose. But if the insect can manage, it extracts

its leg with the pollinarium attached. Then it’s off to another flower and

perhaps another slip into a chamber, where the pollinia are deposited and the

pollen can reach the stigma.

|

| Pollinarium with dangling yellow pollinia on the tarsus (lowest leg segment) of a digger bee. Photo by Allan Smith-Pardo, Bees of the United States, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org. |

That’s a lot of effort, for both the insect and the plant. The reward for the insect, if it isn’t snagged forever in a milkweed flower, is a source of nectar that is almost pure sucrose, the same as in your sugar bowl. The reward for the plant, as mentioned above, is an abundant and directed source of pollen. No other plants but milkweeds can receive pollinia, so little pollen is lost on plants that can’t use it. Even a different milkweed species is unlikely to accept pollinia from, say, a swamp milkweed, because the size and shape of the receiving chamber may not fit the arriving pollinia. Hybrids are therefore uncommon.

To listen to an ecologist talk about milkweed pollination

and why it’s so unusual (and cool!), see this video by Dr. Thomas Rosburg of Drake University for Iowa PBS.

To see milkweed pollination in action, see this video

from the Master Gardeners of Northern Virginia (scroll down at the site) or

another video

from Monarch Butterfly USA. Some of the terms differ, but the process – and the

pitfalls – are the same.

To learn more about swamp milkweed in particular, see this page

from Minnesota Wildflowers.

References

Milkweed pollination biology. By Eric P. Eldredge, USDA NRCS. November 2015.

Milkweed pollination: A series of fortunate events. By Chris

Helzer in The Prairie Ecologist, January 2021.

Wyatt, R. and Broyles, S. B. 1994. Ecology and evolution of

reproduction in milkweeds. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 25:

423-441. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2097319