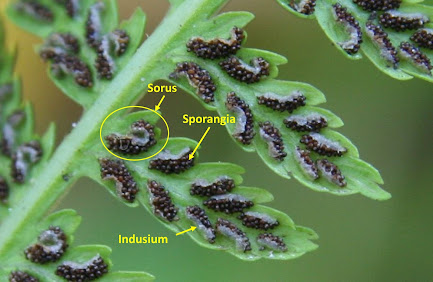

The back of this lady fern frond (Athyrium filix-femina)

is covered with sori, clusters of spore-forming bodies called sporangia. Each

sorus holds dozens of them, all covered by a protective flap of tissue called

an indusium. When a sporangium matures and dries, a line of cells over the top of

the sporangium contracts, causing it to fling open and catapult its spores. You

can watch it happen here

in a sorus of an unidentified fern.

|

| A spore print made by a lady fern frond. The spores are so small they look like dust. |

Unlike seeds, spores don’t contain embryonic plants. They’re

little more than tiny packages of DNA that give rise to the next generation of

ferns. They do this by first growing a small, heart-shaped prothallus, a body

that produces egg and sperm cells. The flagellated sperm cells swim through a

film of water to fertilize the egg cells, which then grow into the ferns we

recognize. Because water is needed for this kind of reproduction, many ferns rely

on damp or humid habitats.

|

| Lady fern is identified in part by the shape of its sori. They are usually curved or horseshoe-shaped. They appear in late summer and early fall. |

|

| Fertile fronds of ostrich fern. |

Both reproductive and vegetative characteristics are helpful

to identify a fern. Here are some resources to learn more about fern anatomy,

biology and identification.

- Ferns. U.S. Forest Service. This site may take a few tries to load.

- Dichotomous Key to Ferns of Wisconsin, by Tim Gerber, UW-La Crosse.

- Key to Fern Traits, by Areca Treon. This is a key to ferns in Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve near Bethel, MN.

- Ferns of Minnesota, by Rolla Tryon. Illustrated by Wilma Monserud. University of Minnesota Press, 1980. ISBN 0-8166-0932-2.

- Ferns and Lycophytes of Minnesota: The Complete Guide to Species Identification, by Welby R. Smith (author) and Richard Haug (photographer). University of Minnesota Press, 2023. ISBN 1517914663.